National Customer Service Week was first championed by the International Customer Service Association (ICSA) in 1984. It was proclaimed a national event by Congress in 1992 and is celebrated each year during the first full week of October. This year, we celebrate the value of the customer service work UFCW members do in grocery stores, pharmacies, retail outlets, and a wide range of other workplaces by taking a look at how good customer service has remained key to a business’s success despite a century of technological advances.

John Kressaty, who was President of the ICSA when the week began, said “There are two main purposes of National Customer Service Week. It lets you recognize the job that your customer service professionals do 52 weeks a year. The other purpose is to get the message across a wide range of business, government and industry that customer service is very important along with bottom line profit in running a business.”

Today, customer service is more important than ever. According to Forbes, “Today, 89% of companies compete primarily on the basis of customer experience – up from just 36% in 2010.“ As one of the cornerstones of customer experience, customer service is not just an old-fashioned idea that “the customer is always right,” but is what sets companies apart and helps them stand out in a field of ever-evolving retail technology.

Everything old is a new again

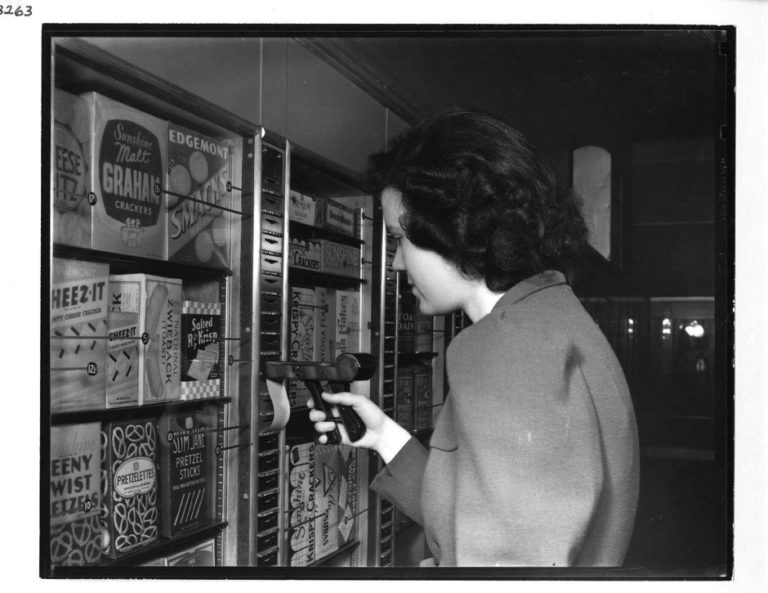

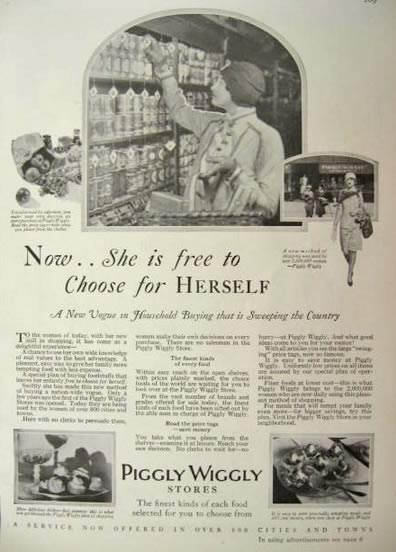

In the beginning of the 20th century, grocery shopping looked very different than it does today. Rather than scour the aisles themselves, customers would hand the grocery clerk a list of the items they were looking for, and the worker would go get the items while the customer waited. But all that changed in 1916 when Clarence Saunders opened the first self-service grocery store, Piggly Wiggly, in Memphis, Tennessee. The new model was advertised as offering more freedom and choice for the customer.

A century later, the same concept of “freedom” to do it yourself has been used to sell other technologies like self-checkout where the customer is expected to do the work that was once done by an employee. And in-store grocery pickup options at places like Kroger, where you can order your groceries online and then an employee will do the shopping for you, aren’t so much a new, revolutionary idea in the industry as they are a return to the way grocery shopping used to work.

Today in Memphis, new technologies are still being tested. Dynasty Brown, a UFCW Local 1529 member, works at Kroger #405 as a picker, one of the workers who shops on a customer’s behalf when the online orders come in. “I like taking the orders out and seeing the smiles on customers faces,” says Brown. A hundred years of progress in technology haven’t changed workers’ pride in providing good customer service, nor shoppers’ appreciation of someone who goes the extra mile for them.

Good technology vs. bad customer experience

As anyone who has ever stood helpless at a self-checkout while it yelled at them about an “unknown item in the baggage area” knows, the “freedom” to do the work yourself isn’t always so free feeling.

A recent article in Gizmodo, “Why Self-Checkout Is and Has Always Been the Worst,” does a pretty great job articulating the difference between good and bad technology, namely that bad technology is the stuff that gets rammed down our throats that no one really wants but we are stuck putting up with anyway:

“For every automated appliance or system that actually makes performing a task easier—dishwashers, ATMs, robotic factory arms, say—there seems to be another one—self-checkout kiosks, automated phone menus, mass email marketing—that actively makes our lives worse.

…

Nobody likes wading through an interminable phone menu to try to address a suspect charge on a phone bill—literally, everyone would rather speak with a customer service rep. But that’s the system we’re stuck with because a corporation decided that the inconvenience to the user is well worth the savings in labor costs.”

But as the article goes on to point out, the promised savings on labor costs for trading out real customer service is often just a long-con by the folks selling the machines.

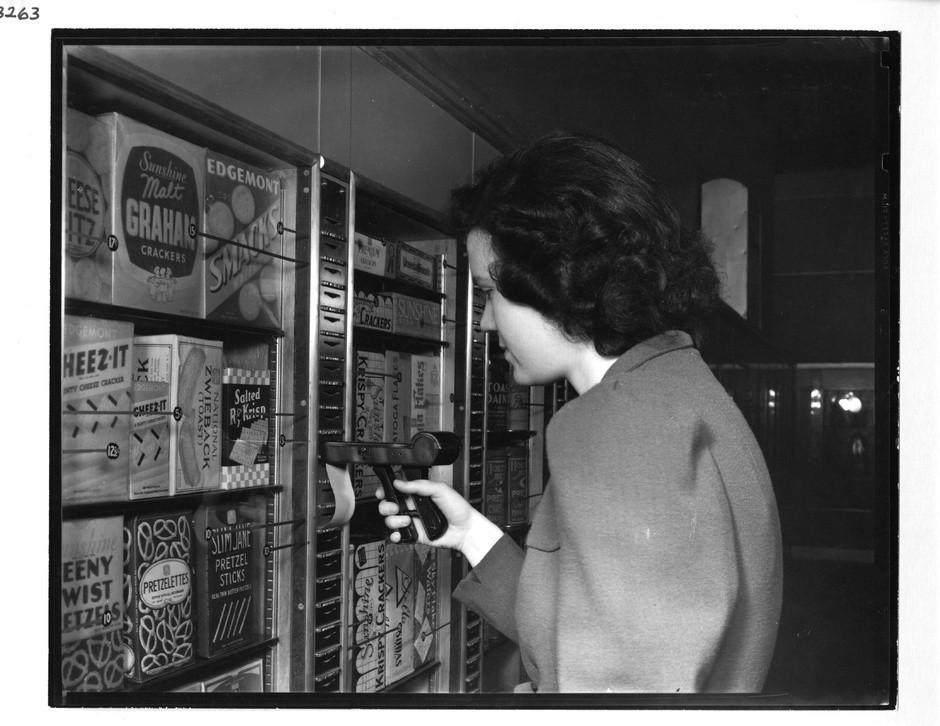

Customers have been rejecting full automation since 1937

Though the announcement of Amazon Go, Amazon’s grocery store model intended to allow shoppers to enter and exit the store without having to make a single human interaction with anyone, made a big splash when it was announced, the first fully-automated self-service grocery store, Keedoozle, was actually opened in 1937 by the same man who started Piggly Wiggly. Unlike Piggly Wiggly, which still operates today (and where many UFCW members work), Keedoozle was a miserable failure.

Items were kept in separate glass cases so as to be easily seen and never handled. Entering customers received an aluminum “key” with a roll of ticker tape attached. They shopped the product windows as they pleased, slipping their key into slots in the displays and pressing buttons that punched Morse code-like data about their desired products. At the checkout, a shopper handed her key to the clerk, who simultaneously rung up the receipt and transmitted the key’s record to a backroom. There, workers bundled orders and sent them out to customers via conveyer belt. ‘It can’t miss. It’s the biggest thing I’ve ever had,’ Saunders told Time magazine. –Americans Have Been Cursing at Automated Checkouts Since 1937

Only it did miss, hard. The last Keedoozle closed in 1949. Saunders wasn’t deterred and went back to work to find even more ways to eliminate more jobs within the grocery store, this time by using an early computer in place of a cashier. Saunders died before the concept got off the ground.

Only it did miss, hard. The last Keedoozle closed in 1949. Saunders wasn’t deterred and went back to work to find even more ways to eliminate more jobs within the grocery store, this time by using an early computer in place of a cashier. Saunders died before the concept got off the ground.

The invisible human labor behind automation

Data & Society’s report, “The Labor of Integrating New Technologies,” finds that rather than replacing jobs, the role out of new shopping technology actually relies heavily on skilled customer service abilities of workers, but those efforts are often invisible and not compensated:

“We find that retail experiments, like self-checkout or customer-operated scanners, tend to rely on humans to smooth out technology’s rough edges. In other words, the “success” of technologies like self-checkout machines is in large part produced by the human effort necessary to maintain the technologies, from guiding confused customers through the checkout process to fixing the machines when they breakdown to quite literally searching for customers aisle by aisle when GPS systems fail. The impact of these retail technologies has generally not been one of replacing human labor. Rather, they enable employers to place greater pressures on frontline workers to absorb the frontline risks and consequences of cost cutting experiments. Much of the work that employees must do on the ground to facilitate new systems is often invisible and undervalued, even as popular perceptions of automation frame these roles as increasingly obsolete.”

The report even points out that senior employees are often needed with advanced skills in “diffusing anger” to help customers navigate new systems and all the bugs that come along with them. But in all the conversations about new technology, this work is swept to the side and seen as exceptional rather than an integral part of both roll out and continued function of self-service technologies.

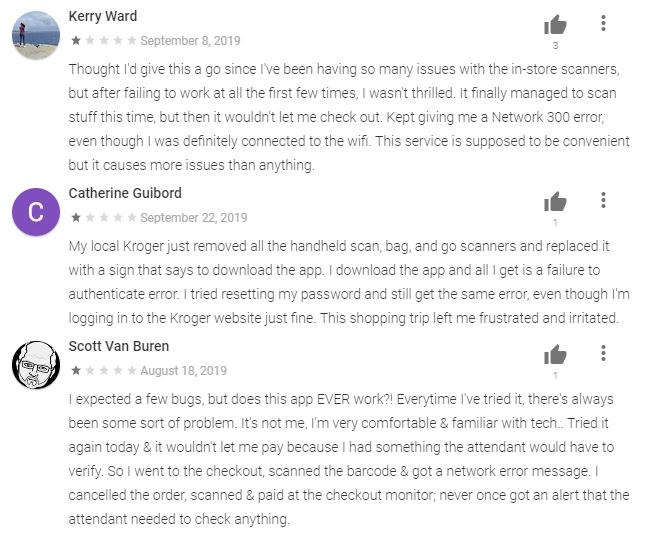

The report lines up with first-hand accounts from UFCW members who work in stores where new technologies like Kroger’s Scan, Bag, Go program have been tested. Scan, Bag, Go allows shoppers to use scanners they carry around the store with them to scan products as they shop. Edith Peck, a UFCW Local 1529 member who has worked at Kroger in Memphis for the past nine years and who says providing good customer service is her favorite part of the job, says that for the most part, customers just ignore the scanners.

“I think this whole thing is Kroger’s scheme to eliminate employees to compete with automation, but at that point, why not shop at Walmart?” says Peck. “They need to understand good customer service is what is going to set us apart.”

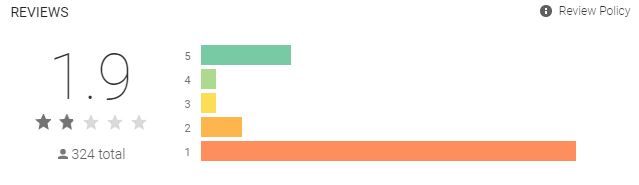

Customer sentiment towards scan and go shopping is pretty clear in the Scan, Bag, Go app, which has a 1.9 star rating in the Google Play store. Reading the reviews paints a clear picture of why “diffusing anger” would be a skill needed to help transitioning customers.

Genuine interaction with cashiers makes us happier

Beyond just the importance to a business’s bottom line, when we talk about the elimination of customer service jobs, it’s also worth remembering to ask: what is it that we want our lives to look like?

A 2013 study, Is Efficiency Overrated?: Minimal Social Interactions Lead to Belonging and Positive Affect, found that that when people engage with cashiers in a genuine way (with a smile, eye contact, brief conversation, etc.), it lifts their mood and leads to an increased sense of belonging. Although people often report reluctance to have a genuine social interaction with a stranger, those interactions still are ultimately good for us. Surprise, just like exercise or eating healthier food, talking to strangers turns out to be a thing we don’t think we want but that makes our lives better when we go out and do it.

Are we comfortable with creating a society where we only interact with products and rarely with flesh and blood people? And given that the answer from most people is a resounding no, how can we effectively push back against technology and innovation that might cross that line while still embracing technology that does improve our lives? If we are so collectively stressed out that saving a few moments waiting in line at the checkout seems like a good trade for someone’s job or our own mental health, perhaps the solution isn’t in improving the efficiency of the shopping experience. Maybe it’s tackling why we’re all so stressed out to begin with.

In the meantime, thank you to all the hard-working UFCW members out there ready to help customers feel seen and appreciated in whatever ways they can, whether it’s service with a smile or repeatedly coming to our rescue at the self-checkout machines. We need you now more than ever.