Union organizing efforts won significant benefits for meatpacking workers during the first half of the 20th century. In 1960, before a wave of automation and rapid restructuring would decimate jobs in the industry, meatpacking wages were 15 percent above the average wage for manufacturing workers in the United States. But one area where change was slow to come was in the poultry industry. Unlike other jobs in meatpacking, a much higher percentage of poultry workers were African American women in the anti-union South.

African American women working at the Eastex Poultry plant in Center, Texas decided to change that in 1953 when they wrote to the Amalgamated Meat Cutters (which later became the UFCW) and asked to join the union. The campaign that ensued revealed the widespread issues with food poisoning related to poultry and resulted in the passage of the Poultry Products Inspection Act in 1957. After tense negotiations between the union and the company, Eastex settled after 11 months, agreeing to wage increases, time-and-a-half overtime pay, three paid holidays and vacations, a grievance procedure, and reinstatement of strikers. Eastex subsequently sold out to Holly Farms, which later sold out to Tyson.

United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) Vice-President Russell R. Lasley (1914-1989) was an officer in UPWA Local 46 in Waterloo, Iowa. He got his start working at The Rath Packing Co. and rose to become one of the central figures in the American civil rights movement. Lasley was a vice president of the international union for more than 20 years, remaining after the UPWA merged with the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen where he became director of the merged union’s civil rights department.

The United Packinghouse Workers of America was one of the most progressive champions for civil rights in the labor movement during the 1950s and 1960s. Formed in 1943, the union began pursuing anti-discrimination activities in 1949 and formed an anti-discrimination department in 1950. The UPWA required every union local to have an anti-discrimination department, and the national union headquarters made certain that the local departments had their own programs in the meatpacking plants and communities.

Together with the union, Lasley fought against housing discrimination in Chicago, according to labor historian Michael Honey of the University of Washington-Tacoma. “He was trying to open up housing for black families in white neighborhoods,” Honey said. “When one home was surrounded and fire bombed, the union brought people out to try to defend the black homeowner. The Packinghouse Workers union was extraordinary. It probably was one of the few unions where whites would really come out and support black civil rights.”

Another leader to emerge from the UPWA was Addie Wyatt, who got her start through union activism and continued her fight for workers’ rights during the height of the American Feminist Movement. She played an integral role in the civil rights movement, and joined Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in major civil rights marches, including the March on Washington, the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, and the demonstration in Chicago. She was one of the founders of the Coalition of Labor Union Women, the country’s only national organization for union women. She was also a founding member of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists and the National Organization of Women.

While Wyatt was working in the canning department at Armour and Company, she was replaced with a white worker who was paid more. The union, which had a non-discrimination clause in their contract, was able to fight the company’s unfair act of discrimination and get her her job back.

“I was impressed,” said Wyatt in an interview with Alice Bernstein in 2005. “How could two young black women meet with two white bosses and achieve the success that we had achieved at that time? I was told that it was because of the union. It was a violation of the union contract…I was really moved to the extent that I wanted to do something to help this union. I didn’t know what the union was. But I know that I needed help and here was the place that I could get that help. I knew that I wanted to help other workers, and I found out that I could help them by joining with them and making the union strong and powerful enough to bring about change.”

In honor of her work, she was named one of Time magazine′s Women of the Year in 1975, and one of Ebony magazine′s 100 most influential black Americans from 1980 to 1984. She was inducted into the Department of Labor’s Hall of Honor in 2012.

One of the greatest moments of the Civil Rights era was the March on Washington in 1963–one of the largest non-violent protests to ever occur in America. The March on Washington brought thousands of people of all races together, in the name of equal rights for everyone–whether they were black or white, rich or poor, Muslim or Christian. Dr. Marin Luther King, Jr. made one of his most inspiring and famous speeches at the march, which culminated on the National mall.

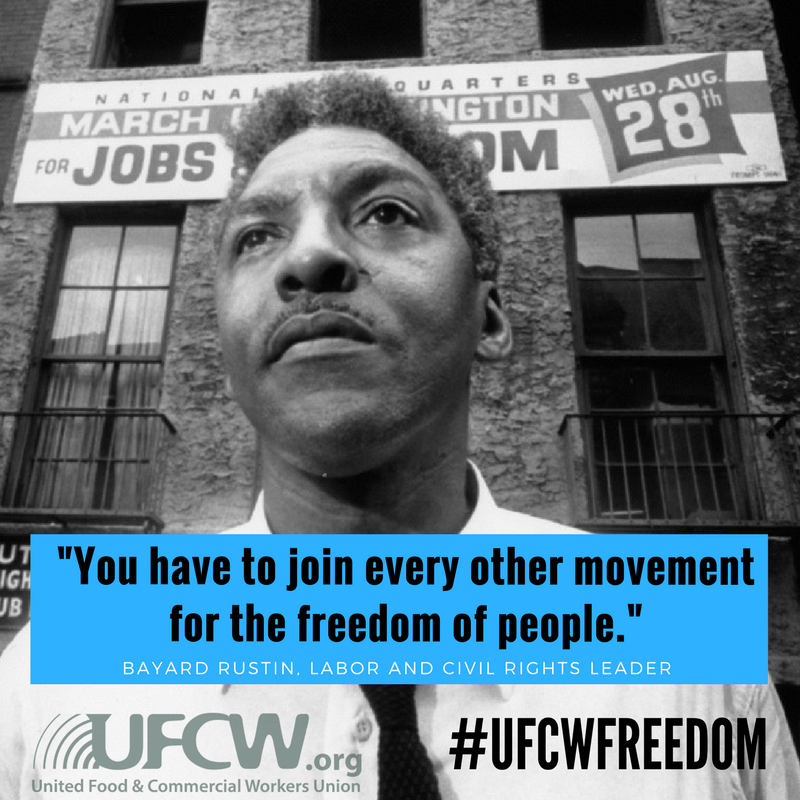

But history has often overlooked the man who was the driving force behind this monumental event–a man named Bayard Rustin. Rustin was the one who organized the march, bringing methods used by Gandhi as well as the Quaker religion to Washington to ensure peace, but also impact. It was Rustin who helped shape Dr. King into the iconic symbol of peace he is remembered as.

Although Bayard Rustin was a tireless activist, his life achievements are unknown to many, and he has even been called the “lost prophet” of the civil rights movement. This is largely because not only was Rustin silenced and threatened like many others were for being a black man speaking out for equal rights, but also because he was openly gay in a time when homophobia and bigotry was rampant. Rustin continued his life as an openly gay man, even after being incarcerated for it, and is seen as a champion of the LGBT movement still today. Despite being beaten, arrested, jailed, and fired from various leadership positions, Rustin overcame and made a huge impact on the civil and economic rights movements.

“We are all one. And if we don’t know it, we will learn it the hard way.” —Bayard Rustin